Blog

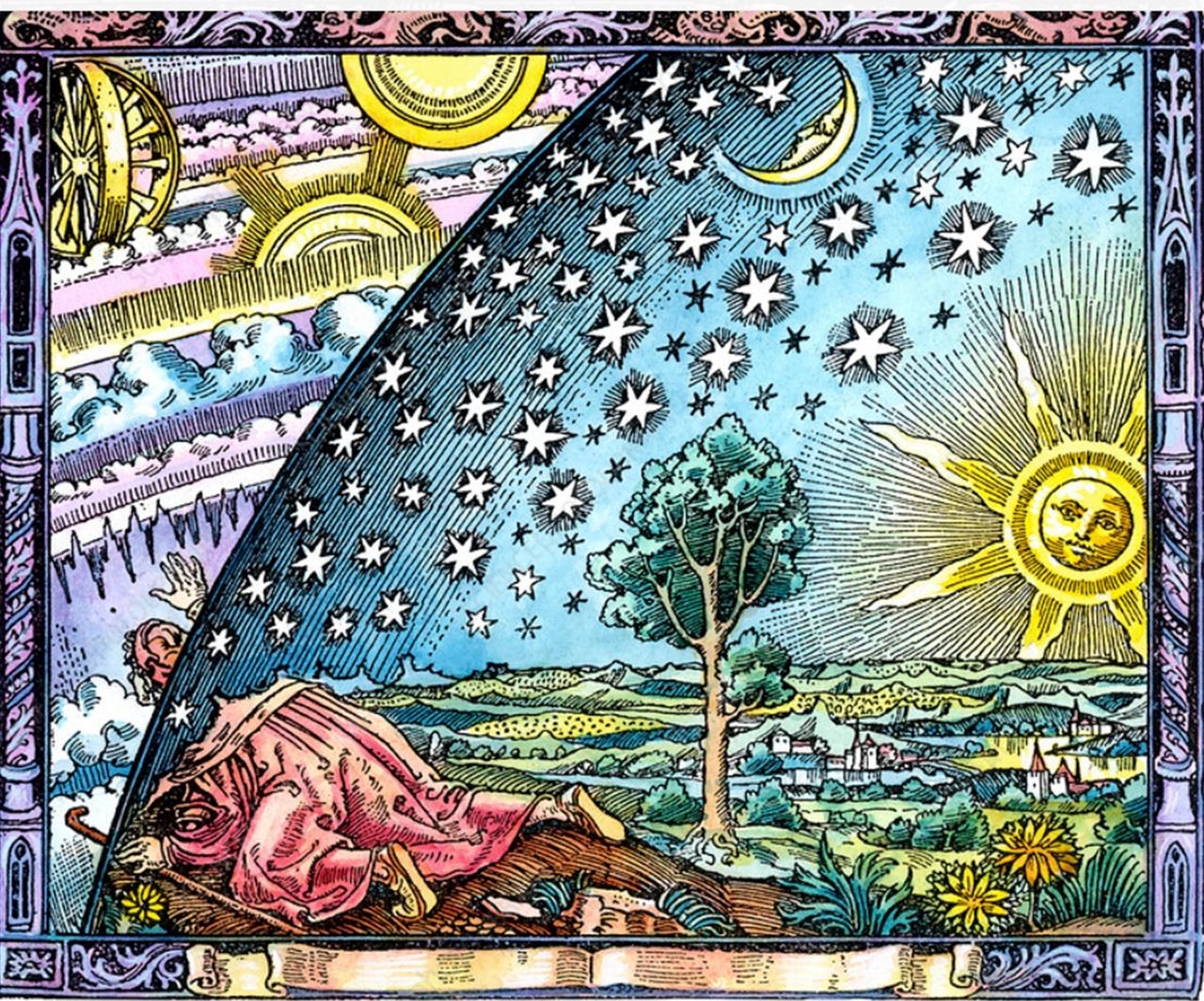

The Italian Renaissance is rightfully recognised as having rediscovered some of the glory of Ancient Greece and Rome. It did not look back to the past impartially but interpreted it through, and ultimately married it with, a burgeoning Christian humanism. Much of the content of these movements forms the basis of what we understand as Western liberal arts (classical) education, and they arguably found their climax in the eighteenth century through another fusion: the French Enlightenment as expressed in neoclassical art.

- Written by: Jonathan Hili

The St John of Kronstadt Academy is a new Orthodox classical school due to open in Queensland in 2024 subject to receiving accreditation through the Queensland Non-State Schools Accreditation Board. The initial intake of students will be from Preparatory to Year 3, with an additional grade being added each year.

(See inside for the sign-up link)

What does it take to homeschool well? How do I find community for myself and my children? How can I give my children the education I didn't receive? What does virtue mean and how do I teach my children's souls? What is Classical Conversations?

Join us for a public lecture with Greg Sheridan, foreign editor at The Australian. His most recent book, Christians, the urgent case for Jesus in our world, became a best seller weeks after publication. It makes the case for the historical reliability of the New Testament and explores the lives of early Christians and contemporary Christians.

29 March 2023, 5:30pm for 6pm start.

Cheree Harvey

With her dying breath, Rachel named her newborn “Son of My Sorrow” (Gen. 35:18). Jacob knew that this would be a terrible legacy, so he renamed him Benjamin - “Son of My Right Hand.” What a difference!

21-22 April 9am - 4pm (AEST)

When we search for harmony, coherence, or meaning in our public discourse we are tempted to give up in despair. Increasingly, our age seems to believe the world itself has no meaning or coherence. On the one hand, they see it as liberation: it means we are free to choose ourselves and make our own meaning. On the other hand, it means that in a world of mechanism and force, each of us is on our own. Freedom is an escape from reality into chaos. Meanwhile, virtue is as needed as ever, but the path to its discovery is lost.

[Download brochure - PDF 2.33MB]

An online five week course examining the thoughts of the ancient thinkers: the Presocratics, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Aurelius, for their impact on the formation of Western thought. We compare and contrast their views of reality focusing particularly on concepts such as teleology, being, the soul, virtue, the social and creative nature of persons, and how we ought to live. We explore theories of human nature, human behaviour and instincts, ethics, personality, and identity.

As one of the members of the Australian Classical Education Society who recently completed a three-month training for Paideia Pedagogy Certification with Dr Robert Woods through Kepler Education, I want to put this training to work by starting an online book club for children (ages 7 – 11).

Join ACES for immersive classical pedagogy sessions with practical classroom application.

Saturday, 1 April 2023 8AM-12PM (AEDT) 7-11AM (AEST - QLD)

Download Conference Flyer [PDF 309KB]

The Liberal Arts Tradition is a foundational work that provides an excellent overview and insight into how the Classical education movement can bring to life educational traditions and principles in the 21st century. This week our book club continued with our discussion of Part III of the book, dealing with Philosophy as it sits above the 7 Liberal Arts.

Jemima Ayoub

As a year 12 student, school has been a common denominator in every aspect of my life for almost as long as I can recall. From my very first day of prep, my enthusiasm to learn only ever grew, as my thirst for contestable knowledge flourished through the nurture of the critical thinkers whom I was privileged to be surrounded by.

Today ACES held its second online AGM. So much has been achieved in the last 12 months. Here are just a few of our achievements:

- Written by: Kon Bouzikos

Patrick Long

A few years ago, I found myself more frequently saying that ‘there has to be a better way’. Recent polls and surveys suggest I was not alone, and the sentiment is shared by many today: 44% of US K-12 Teachers feel burned out (Gallup Poll, 2022), with another poll finding the 2 out of 5 teachers plan to quit in the next two years; 22% of UK teachers plan to leave within the next five years (The Guardian); and up to 30% of teachers in some parts of Australia feel the same way (president of the AEU). Indeed, that sentiment was a large factor in my leaving mainstream education in the UK for a smaller, independent Catholic school in France.

Martin Keast

Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right. “Honour your father and mother” (this is the first commandment with a promise), “that it may go well with you and that you may live long in the land.” Fathers, do not provoke your children to anger, but bring them up in the discipline and instruction of the Lord. (Ephesians 6:1-4, ESV)

The word ‘paideia’(παιδείᾳ) is a Greek word used in Ephesians 6:4 which is usually translated ‘discipline’ as in the ESV above. Paul is here requiring parents, under the headship of the father, to bring up their children in the ‘paideia of God’. This term is a very significant one in 1st century culture and we sometimes miss the richness that this imperative involves and its application to Christian and classical education. Doug Wilson, one of the early pioneers of the modern classical revival in Christian educational circles, wrote an essay entitled “The Paideia of God” which explored this richness (Wilson, 1999). I wanted to share some of these insights as a contribution to what I hope is the beginning of a classical renewal here in Australia.